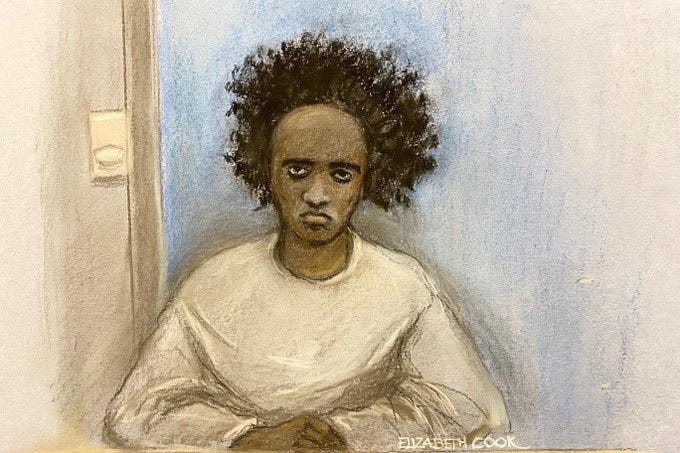

'Mute of Malice'

Why has Axel Rudakubana shown his face?

Now, there can be no excuses. There is a courtroom drawing of Axel Rudakubana as an adult, his face uncovered, in the public domain. Any newsmedia outlet who, henceforth, touts images of Rudakubana as a child demonstrates themselves to be enemies of the victims and enemies of the public.

After an almost four hour delay in which he claimed to be sick, Axel Rudakubana appears in Liverpool Crown Court via video link.

The time is 2:16 PM on 18 December 2024. The teenage accused of murdering three young girls and the attempted murder of ten others, Axel Rudakubana, sits facing the camera in his grey prison-issue tracksuit. For the first time since proceedings began his sweater is not pulled over his nose or mouth, and the court is able to see his face.

He is clean shaven. “His face was crystal clear. He is very, very dark skinned” recounts one reporter in the public gallery. “His face is childlike and his hair has doubled in size since his last appearance.”

For some of the parents, this will be the first time they have seen the face of the man who is accused of mutilating and murdering their daughters…

Rudakubana is asked to confirm his name but does not speak.

The court clerk asks prison staff to confirm that proceedings can be heard.

“Mr Rudakubana can hear you,” replies a guard, and Rudakubana is asked again to confirm his identity, but he remains silent.

Early in proceedings, Rudakubana could be seen fidgeting with his hands. In the reading of the three murder charges — Elsie Dot Stancombe (7), Alice da Silva Aguiar (9), and Bebe King (6) — Rudakubana is silent and sways side-to-side. He makes no motion to speak when the further thirteen charges are read to him. As the judge communicates with the defence about extenuating circumstances, he becomes restless. Are their any applications for diminished responsibility due to mental incapacity or illness? There are none.

Future arrangements are made and confirmed by the judge — including a bad character evidence hearing and a prison transfer. Throughout, Rudakubana has his head bowed and his arms crossed until the proceedings are concluded at the video link is terminated.

What are onlookers to make of this subtle shift in Rudakubana’s behaviour?

Whilst the accused continues to exercise his right to remain silent, there has been a meaningful departure from his face-covering behaviour. Why?

Whilst there is no hard rule banning a defendant from covering his face with his hands or clothing, he who is giving evidence, being addressed, or questioned is expected to show his face to the court. Head and face coverings are not permit in court, with exemptions being made for reasons of health and religion. A failure to show one’s face when requested can lead to a charge of contempt of court.

Over the last decade there has been an evolving argument over face and head covering in courtrooms. Attempts have been made to accommodate the religious mandate of Muslim women to cover themselves in public and not be seen unveiled by members of the opposite sex, and satisfy the judge and jury’s need to see the defendant as they give evidence.

"The ability of the jury to see the defendant for the purposes of evaluating her evidence is crucial,” Blackfriars’ Crown Court judge, Peter Murphy, has perviously ruled. Some maintain that this constitutes a violation of the defendant’s human rights. But Keith Porteous Wood, executive director of the National Secular Society, and British solicitor Joshua Rozenburg KC have stated that it is "vital" defendants' faces were visible at "all times."

At best, Rudakubana’s face covering is discourteous to the court and offensive to the victims and their families who are obliged to bare their own grief-stricken faces to the pubic. At worst, this constant masking of his face could amount to a contempt of court charge for Rudakubana, if the judge has previously warned the defence counsel against this behaviour.

When the prison reported Rudakubana ill on the morning of his plea hearing, the judge — Mr Justice Goose — could have made the easy decision to suspend proceedings until Rudakubana had recovered, or otherwise became more obliging to the court.

With the court backlogs stymieing the justice system, there is no doubt pressure upon judges to swiftly move onto the next case if associated figures fail to attend their allotted time slot. Indeed, this outcome had been so much anticipated that journalists began to leave the court after clerks announced a hesitant postponement to two o’clock.

It was with substantial surprise, then, that Rudakubana not only showed up to the trial but had ceased to cover his face.

It seems the judge has put his foot down, insisting upon the strict adherence to procedure and standards of curtesy. After holding the court for four hours, waiting for Rudakubana to appear, Mr Justice Goose remarked that Rudakubana was “mute of malice.”

This is the legal definition for a defendant who wilfully refuses to speak.

This is significant. With this statement, Goose announces that in his professional opinion Rudakubana maintains his right to silence not out of self-protection but out of obstinacy — disrespect and contempt.

Rudakubana has been deemed to ‘fit to plea’. When the time came for the defence counsel to speak, they offered no defence statement, no psychiatric evidence, and no application for admissibility. In other words, there is no “get out” clause. Platitudes of “mental illness”, “vulnerability”, or “compassion” will not easily be accepted by the court, and there will be little sufferance of obstinacy, complacency, or disrespectful behaviour.

It felt like a clear message and refreshing message was sent out by the judge: “I will not tolerate any playing up.”

Firm but fair?

This insistence upon courtroom etiquette does not mean the judge is biased against Rudakubana or that he is holding Rudakubana to unreasonable standards.

An unwavering adherence to the rules is often considered cruel, unjust, or discriminatory these days, rather than an expression of equal treatment before the law. Knowns to some as “equity” and known to others as the “bigotry of low expectations”, it has been touted around that those belonging to one or more minority groups must not be subject to the same rules as the dominant demographic in society (that demographic typically being “straight, white men”).

Individuals belonging to such minorities deserve special dispensation — a pardon from certain rules. This is because they cannot be expected to adhere to those rules on account of some immutable aspect of their identity which is incompatible to the rules. The more “minorities” to which a defendant belongs, the more leeway he or she can expect to enjoy.

Dispensation is sometimes justified. Children, for example, who are convicted of committing a crime receive more lenient sentences than adults accused of committing the same crime. Those suffering from a severe learning difficulty or a psychopathology are also treated with digression by a court, it being acknowledged that the individual in question may not be in possession of their thoughts and emotions for substantial amounts of time.

There are, however, an increasing number of appeals for leniency which contradict a fair judgement. Special dispensations, instead, seem to taunt victims and humiliate the judicial system.

“Cultural context” is one example of this overly generous attitude to difference. In Spain 2022, a man was arrested for impregnating a 12 year-old girl. The prosecution sought a prison sentence of eleven years and six months. However, the man was acquitted after the court noted the victims' ethnicities and "cultural context". They stated that sex with “consenting” children "in Romani culture, this is normal behaviour."

In this instance the defendant — who would otherwise be branded a criminal — is also regarded as a victim. He is a victim of a judgemental and bigoted culture who would persecute him for something that is ordinary in another land.

Claims of mental illness are also cause for immunity from the law. This concession has been invoked with such frequency in recent years that it has become a trope among the People. Otherwise known as “pulling the mental health card,” a defendant makes false or insubstantial claim to mental illness and argues, therefore, that he is irresponsible for his actions.

An Eritrean man convinced of raping a fifteen-year-old girl was granted leave to remain in the United Kingdom after he argued that deportation would harm his mental health. The man had been well enough to campaign against detention for unprocessed asylum seekers, but his lawyer claimed he would commit suicide if he were deported and that deportation would, therefore, go against his human rights.

In this instance, the criminal is victim as well as a perpetuator, for the cruel and unfeeling British would have him be subject to the laws of his own barbaric land, where he would not be afforded the same consideration and leniency. It does not matter if his disclosure of suicide is a mere threat. The very fact that he felt compelled to lie indicates that he is a poor and forgotten individual and it is the job of good and caring people to nurture such people, and supervise the lives of those who are unable (or at least unwilling) to manage their lives for themselves.

One might cry out, “What of the victim’s human rights?” But it seems this is given little consideration.

Victims are almost considered an annoyance for the Establishment — the government, media, and their extended apparatus — for the victim has brought this unsavoury person to the attention of both the State and the public. In making an allegation of crime, the plaintiff indentures the State to conduct criminal proceedings, with all allegations (in some capacity) being a reflective allegation of poor management upon the State itself.

These “social justice” rulings are cultured from deep wells of “compassion” and “understanding” fetched forth for the offender by a court and a sympathetic press but leave the victims and their families desiccated.

Why did it take this long to see an image of Rudakubana as an adult?

It is customary to withhold the official mugshot of a suspect until after a trial has concluded and the accused has been found guilty. This does not explain why no picture of Axel Rudakubana as an adult had been circulated for press use — only images of the accused as an eleven or twelve-year-old schoolboy.

Some believe in covering his face Rudakubana is masking a beard — a theory from which people have since been dissuaded. I am inclined to believe he was masking a smile. Those close to the case believe an up-to-date photo or drawing has not been circulated because the image of Rudakubana might prompt memories in the wider Southport community…

His school-boy image often features beside pictures of the three primary school girls who were killed — Elsie Dot Stancombe, Alice da Silva Aguiar, and Bebe King — as if Rudakubaba himself were among the victims.

The Establishment — the Police, Government, Courts, and Media — must have recognised the insult this vulnerable and childlike presentation of Rudakubana would have been to the victims and families? Only now do they seem to realise, after months of public outrage, that withholding this image, and presenting an entirely different one, looks suspicious. Perhaps, it is an attempt to assuage these inextinguishable rumours of state interference and media collusion, that this drawing of Rudakubana, as an adult with his face uncovered, now been released to the general public.

What remains to be seen is why the media felt compelled to construe Rudakubana in boyish and vulnerable terms in the first place? Whilst a picture of him as an adult could not be published until he became an adult, why present him as a similar age to the victims rather than sixteen or seventeen? While the presumption of innocence must be maintained, even in the most trying of cases, must innocence be belaboured to the point where it obscures guilt?

Great concern has been leavened about compromising the trial — in prejudicing the jury, and condemning the accused before the trial takes place. From the night the incident, the public and the Press were warned: to discuss the case in any capacity could compromise the integrity of the trial. When that failed to produce sufficient silence upon the matter, the public were, shall one say, reminded that a contempt of court charge carries up to a two year prison sentence.

It is recognised that Britain’s laws around media commentary on crime are harsher than other countries, like the United States. Rather than lockdown a jury ahead of the trial, the decision was made, it seems, to lockdown the country instead. Stifling conversation among public officials, publishers, and commentators, but also among the public themselves, has led to significant concerns about a “cover up”.

Members of the public have been visited by police in their homes as a result of their online comments about the case. Following the summer of arrests, where non-violent protesters as well as violent rioters were coerced in accepting prison time on the advice of their lawyers. They were told that pleasing guilty would result in less time in incarceration than waiting for a trial.

Fear among the British public is substantial. In online discussion forums — like X and Facebook — one can readily see individuals policing one another’s speech, warding each other away from discussing Southport and Rudakubana. “Be careful,” they say, “You’ll jeopardise the case” or “you’ll be arrested.”

But it is not only the public and media who are now subject to constraint. After the reading of the second charges laid against Rudakubana — the production of ricin and possessing a version of an Al-Qaeda training manual — Parliamentary privilege was revoked to inhibit questioning and debate. Parliamentary privilege is a legal immunity enjoyed by members of the British Parliament which enables them to speak and carry out their duties free from interference. It is regarded as one of the central pillars of maintaining an accountability democracy.

Regardless of veracity of these contempt of court proclamations, the Press have refused to publish material that lies outside that which the Police have handed to them. Attempts even to elucidate upon the meaning of those facts presented to the public by the Police have been quashed. For myself, I had been invited onto GB News by Mark Dolan to lay out, “What kind of things does ‘contempt of court’ prohibit the public from discussing?” After some six hours of back and forth between the channel higher-ups and the legal team, the segment was pulled from that evening’s broadcast schedule.

Chief Constable of Merseyside Police — Serena Kennedy — has assured the public that online “speculation” suggesting “the police are deciding to keep things from the public…is certainly not the case.” It is only, that the police “are restricted in what we can share with you now.”

There are no commands for silence from the top. It was mere serendipity that no mainstream media outlet published a report when Rudakuaba’s plea hearing had been delayed. Perhaps the most horrific attack against children in the United Kingdom since the Manchester Arena bombing appears, to the mind of the Press, not to be in the public interest.

Yet, there has been little concern expressed for biasing the court towards Rudakubana’s innocence. DNA evidence might place him at the scene with the blade in his hand but if the jury believed he was a vulnerable boy, a second-generation immigrant, unmoored from any sense of place, bullied, and autistic, they might resolve he bears limited culpability for his actions.

There is little concern about how our suicidal empathy — being compassionate to the point where one opens oneself or ones’ society to deadly harms — could jeopardise securing a just outcome for the victims and families.

Had Prime Minister Keir Starmer — a master barrister and ex-director of Public Prosecutions — been concerned about prejudicing trials of online protesters and street rioters when he declared to the nation they had participated in “far-right thuggery”? Had he considered how his characterisation of protesters might impact the public’s view of Rudakubana — construing him as a victim of racism and prejudice ahead of the trial?

Is this narrative control then about preserving the Peoples’ right to a fair trial?

It is a valid question to ask under the circumstances.

After being in conversation with my peers and colleagues, I believe that many journalists, particularly those whose politics are right of centre, are naturally but disappointingly scared of imprisonment. They are, by instinct, believers in the good of higher institutions of Government, Police, and Law, and are cautious of violating something sacred. They believe the potential for a mistrial is a real and significant risk and are terrified — as fathers, mothers, sisters, brothers themselves — by the prospect that they could ever play a part in such a tragic outcome. I share in their paranoia, despite my better knowledge, for I believe being right about this case offers little immunity from State harassment.

There are those journalists and public officials, however, who are less afraid of a mistrial than the public reaction to courtroom revelations. They know social cohesion will take a palpable hit and tarnish the good name of “multiculturalism”. In protecting these phantom causes over the ghosts of these murdered girls, these publishers demonstrate themselves to their enemies, and the enemies of all parents. They are unholy priest who makes a blood sacrifice of own child.

For these writers and these politicians have children of their own — girls the same age as those who were killed and mutilated. The Prime Minister himself. It cannot be that they fail to see the victims of the Southport massacre in the beaming faces of their own offspring. They cannot believe they and their children would be immune — not forever.

It is incumbent upon each and everyone to demand an answer to the question:

Why does ‘multiculturalism’ matter more?

Makes one wonder just what "they" have got to hide and who is included in "they"?

It cannot be a coincidence that Starmer has spent an extraordinary amount of time travelling outside the UK, as if he is making a bid for some form of European/International role?

Could it be that he will be toast at some point soon?